projects

A Methodological Framework for Free and Open-source UAV-based Archaeological Research

Advances in Archaeological Practice

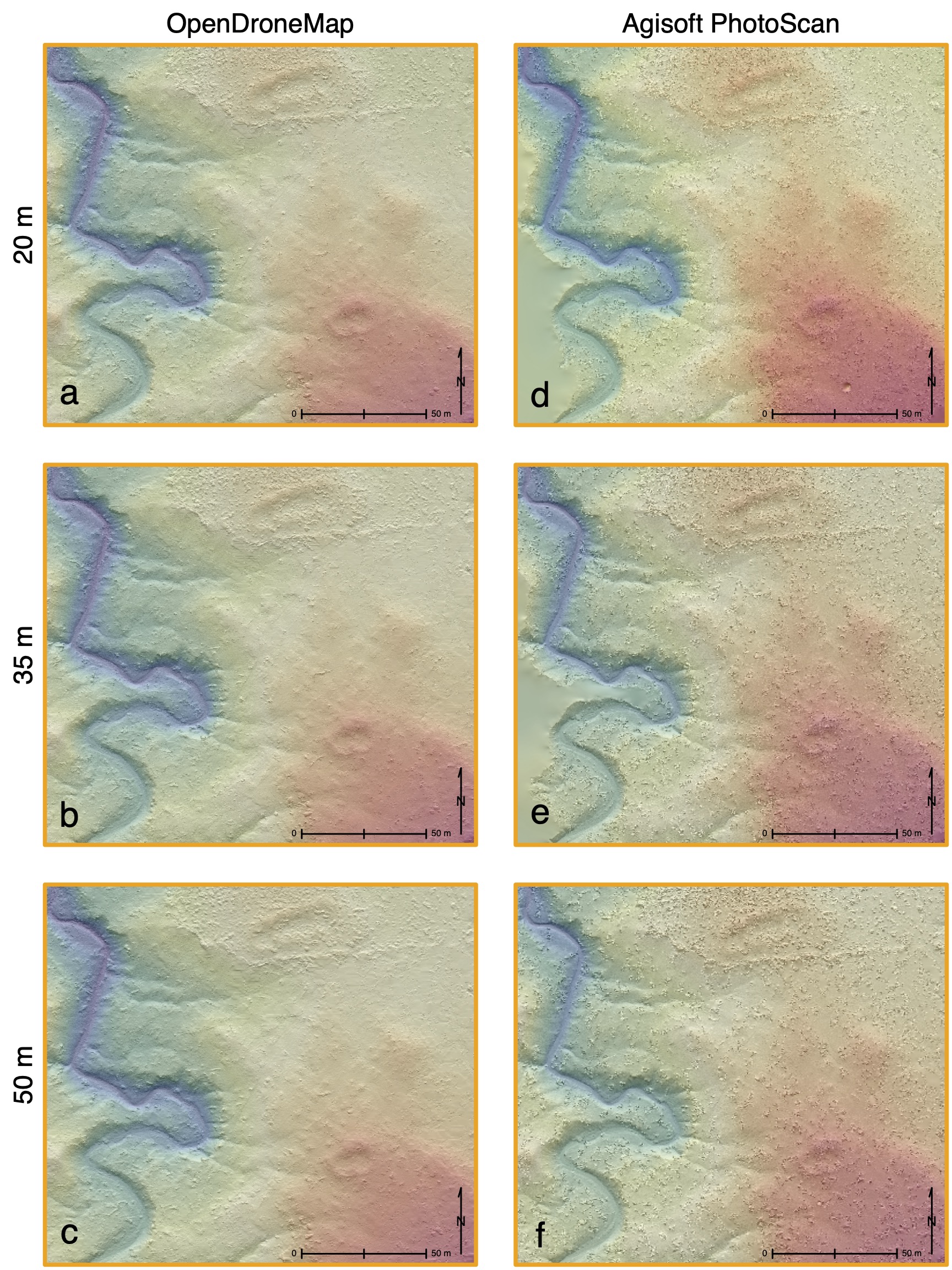

Full-coverage pedestrian survey to record cultural features on unexplored archaeological landscapes is costly in terms of time, money, and personnel. Over the past two decades, researchers have implemented remote sensing and landscape data collection techniques using Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) to combat some of these burdens, but the initial cost of equipment, software, and processing power has hindered the ubiquitous implementation of UAV technology as an accessible companion tool to traditional archaeological survey. This paper presents a free and open-source, technology-independent analytical framework for the collection and processing of UAV images to produce high-resolution digital terrain models limited only by the equipment available to the researcher. Results from the free and open-source protocol are directly compared with those produced using proprietary software to illustrate the capabilities of freely-available data processing tools for UAV-collected images. By replicating the methods outlined here, researchers should be able to identify and target areas of interest to increase fieldwork efficiency, decrease costs of implementing this technology, and produce high-resolution terrain models to conduct spatial analyses that pursue a deeper understanding of cultural landscapes.

Deep Learning Artificial Neural Networks for Non-destructive Archaeological Site Dating

Journal of Archaeological Science

This article introduces artificial neural networks as a computational tool to utilize legacy archaeological data for precisely and accurately estimating dates of residential site occupation. The implementation of this deep learning algorithm can provide high-resolution demographic reconstructions of a study area from non-collection, non-invasive, and non-destructive data collection methods that only record frequencies of artifact types on the contemporary ground surface. The utility of this deep learning algorithm is presented through an example from the central Mesa Verde region in the northern US Southwest. Results show a properly trained artificial neural network predicts annual residential occupation with an average 92.8% accuracy from AD 450–1300. An annual demographic reconstruction of the central Mesa Verde region using occupation predictions from the artificial neural network is also presented.

Check Dam Agriculture on the Mesa Verde Cuesta

Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports

Prehistoric water management in the northern US Southwest was integral to successful subsistence. On the Mesa Verde cuesta in southwestern Colorado, several types of water management features have been identified in the archaeological record, but research into these features has typically focused on the efficacy of reservoirs—a large-scale, labor-intensive, and community-oriented means of collecting and storing water. This focus on large-scale water management features has largely ignored the productive potential of small-scale and low-cost strategies for water management executed by individual households. There is considerable evidence, for example, that extensive check dam networks were constructed and used on the Mesa Verde cuesta, but their actual utility as a small-scale risk-aversion strategy to resource stress has not systematically been explored. This paper identifies all ephemeral drainages on the Mesa Verde cuesta where check dam construction was possible, then applies a maize growing niche model to estimate total yields from check dam farming plots for each year from AD 890–1285. A demographic reconstruction is then used to estimate the percentage of the total cuesta population that could have been supported using only check dam maize yields through time. Results suggest that check dam farming could have supplied a reliable source of surplus annual maize sufficient for household storage needs even during the most populous time periods across the cuesta landscape.

Dynamic Communities on the Mesa Verde Cuesta

American Antiquity

This paper systematically and quantitatively characterizes interaction dynamics and community formation based on changes in spatial patterns of contemporaneous households. We develop and apply a geo-spatial routine to measure changing extents of household interaction and community formation from A.D. 600–1280 on the Mesa Verde cuesta in southwestern Colorado. Results suggest that household spatial organization was shaped simultaneously by the maintenance of regular social interaction that sustained communities, and the need for physical space among households. Between A.D. 600 and 1200, households balanced these factors by forming an increased number of dispersed communities in response to increases in population and variable environmental stressors. However, as population rebounded after the mid-1100s megadrought, communities became increasingly compact, disrupting a long-standing equilibrium between household interaction and subsistence space within each community. The vulnerabilities this change in community spatial organization created were compounded by a cooler climate, drought, violence, and changes in political and ritual organization in the mid-A.D. 1200s, which ultimately culminated in the complete depopulation of the Mesa Verde cuesta by the end of the thirteenth century.